Anyone who works in schools, whether as a performer or a full-time teacher, knows the importance of flexibility. It is probably the most important character trait needed to work successfully with children. Children present adults with surprises and challenges almost every hour. And when your workplace is filled with 400 or more children, from kindergartners to sixth graders, a typical day is always atypical.

No one knows this better than professional assembly show performers. Most presenters invite kids on stage during their shows, opening the door for fun interactions, wild improvisations and sometimes unexpected challenges.

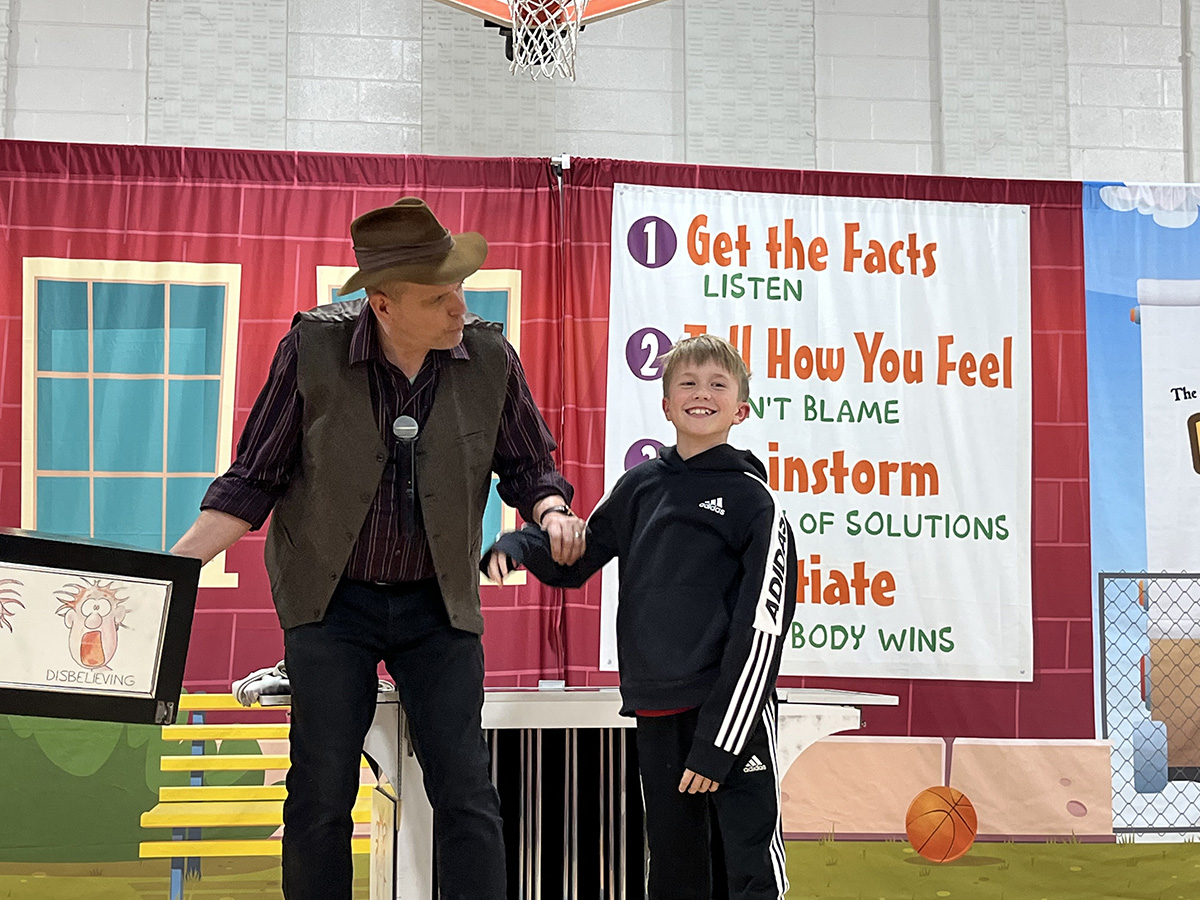

Uncooperative volunteers are rare. Most students know they’re lucky to be on stage in front of all their friends and teachers. Being chosen from a group of over 400 kids is like winning the lottery for some. They’ll be on their best behavior because they don’t want to do anything that could embarrass them.

It’s unlikely that this is the child’s fault. Think about this for a moment. Imagine you’re 7 or 8 years old. You’re standing on a well-lit stage with everyone staring at you. You’re under 800 watchful eyes, and stage fright sets in. It’s easy to understand why you can’t pick up the stranger’s instructions quickly. You think, “What did he say?” Maybe you’re too shy to say you didn’t understand something, or you’re distracted by your friend waving at you from the audience. Presenters don’t want that. The simple solution to this problem is for the presenter to word the instructions carefully and as efficiently as possible, without extraneous words or complicated steps. Most often, young volunteers are asked to do simple tasks anyway: “Stand here, hold this, wave this, say this.” Asking students of any age to do more than one simple task while under the pressure of the spotlight may be asking too much. Psychologists know that children have a hard time remembering multiple instructions that are given at the same time. Parents know that telling their young children, go upstairs, put on your pajamas and brush your teeth is way too much for a child to remember. Performers need to understand this too. The “keep it simple” rule should always be followed when directing young children on stage.

Performers must be careful not to jump to conclusions about why children are “defiant”. Sometimes (and this is quite common) a child may not understand English. As more families immigrate to the U.S., children who don’t speak English are integrated into classrooms. With patience and a big smile you can handle these situations, and the teachers will be impressed with your professionalism. Once, a teacher sprang into action to help me when I was a talking to a non responsive young boy. The teacher pushed another child toward me, not as a replacement, but as a translator. It was adorable watching a first grader translate my questions to his little friend.

Performers must also be aware of the social interaction difficulties that more and more children have. If a child is invited to join in but has difficulty making eye contact with you, this could be an indication of a deeper issue. For advice and tips, see my earlier blog on working with children with special needs.

Often, assembly performers can look into their audience and see some kids who are just there to fool around. While this rarely happens, it may in older grades, especially when there is a substitute teacher watching over the class. Giggling, pointing, and whispering to each other are unmistakable signs that these kids should not be selected as on-stage helpers during the assembly performance. A smart performer can use some of the techniques described in the blog on dealing with disruptive children to mitigate the distractions caused by these children.

However, if you intentionally or accidentally choose one of these children, you may be headed for trouble. Children should be carefully selected. Always watch the audience and find the children who are watching attentively, smiling, laughing and seem full of joy. These well-behaved children deserve their place in the spotlight and should be rewarded with time on stage. However, if a well-behaved child is invited on stage and suddenly refuses to participate, the performer should immediately ask the child if he or she has changed his or her mind about helping. Sometimes the child will say “yes”, and that is fine. The child can be quietly excused with the comment, “Jonny changed his mind and that’s okay”. If the child says, “No, I want to help,” this is usually the only thing that needs to be said to get the child to cooperate. This interaction should not embarrass the child so it should be spoken into the microphone for all to hear. Over the microphone, the child is promising the entire audience that he or she will follow the instructions and now behave.

When the next volunteer is selected, the performer can gently remind the entire audience that anyone who is selected is being asked to cooperate by performing some simple tasks. If they agree, they should raise their hand to help.

If the volunteer is just being disruptive or unfocused, it may be best to just press on. But if the child is ruining the routine, it is time to excuse the child. An effective and non-awkward way to do this is to put the microphone aside and tell the child that he or she has finished and needs to return to his or her seat. Then the performer can say over the microphone, “Jonny has changed his mind, and that’s fine. Who would like to step in as his substitute?” Then another child can be chosen. The child is not shamed and the segment can continue.

The best teachers will approach you after the show with the troublemaker in tow to apologize. When that happens, it’s best to empathize with the child. In those instances, I like to say, “I think you were just trying to be funny because I used to be like you. And it’s great to be a funny kid. But at some point I had to learn that there’s a time and a place to be funny. You picked the wrong time today. Maybe you learned that, too. Can you remember for next time? Thank you for apologizing.”

Some students raise their hand to volunteer, even though they secretly hope they will not be chosen. They do this because all their friends do it too and they do not want to appear afraid or cowardly. No performer should ever try to encourage a child to assist as some adult performers do. All performers learn by watching other experienced performers, but in the world of corporate entertainment it is not uncommon for a performer to say, “Oh, come on. Don’t be reluctant. How about we encourage her with a round of applause?” A children’s performance is not the place for that. Children are different from adults and need to be respected accordingly.

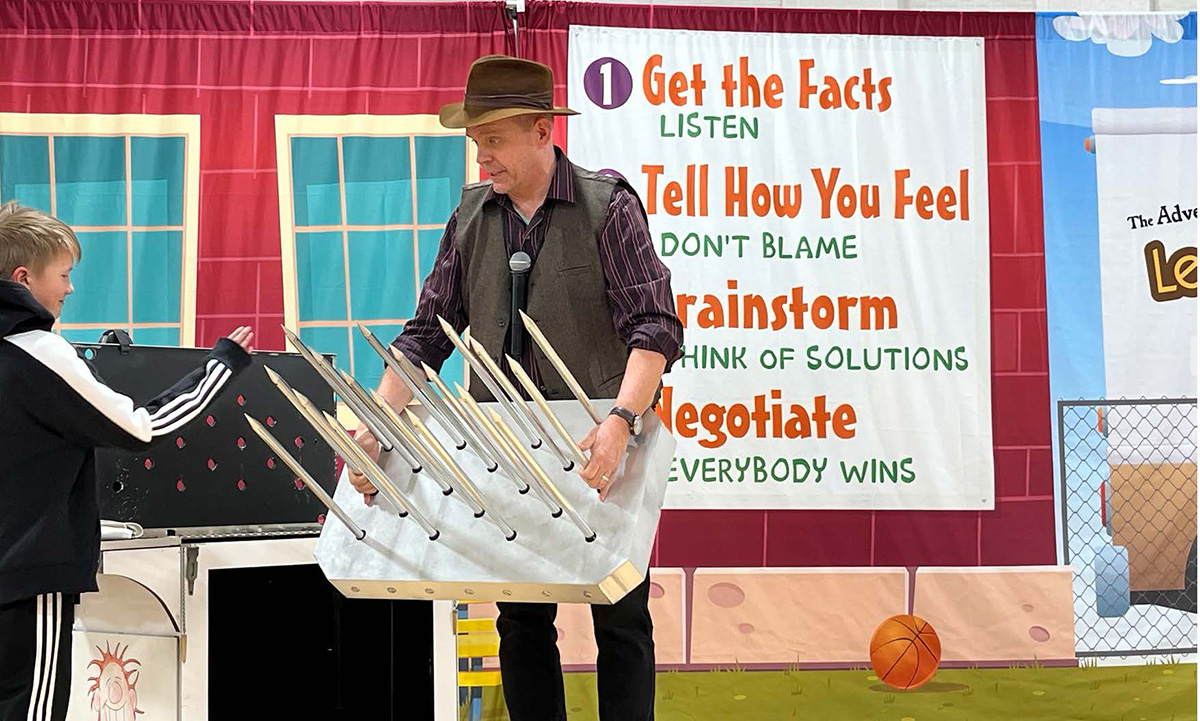

This usually happens when the performer brings out a prop that looks intimidating or introduces an animal that the children don’t want near. Trying to force the children to participate is the worst thing a performer can do. Performers must be compassionate, but before asking for a substitute volunteer, the performer can try to reassure the child that he or she has nothing to fear and that he or she’ll be 100% safe. The child shouldn’t be pressured in any way, and should be told that it’s perfectly fine if they change their mind. If a child wants to return to her seat, again the performer should say, “Suzy changed her mind about helping. Let’s give her a round of applause for trying.” Then another child can be chosen.

In one of my assembly shows, we perform an illusion called Audience Acupuncture. This involves an artificial bed of nails, which can be very intimidating. Even though the kids are told it’s a harmless Halloween decoration, about 1% of our volunteers bow out of helping once they see the prop.

However, when we successfully complete the illusion, after sending the first volunteer back to their seat, I deliver one of my favorite messages. It goes like this, “Wow, that was fun. Thanks to our brave volunteer Billy, we learned a lot about feelings. If you think Billy was brave, raise your hand. Great. If you think our first volunteer, Suzy, was brave too, raise your hand.” Lots of hands go up. Then I turn directly to Suzy and say, “Suzy, you were the bravest, and I’ll tell you why. You taught everyone here today that in situations where you’re scared or uncomfortable, it’s best to say you don’t want to do something. You told me about your feelings, and that was very smart of you. No one should ever make you do something you don’t want to do. Telling me you wanted to go back to your seat was incredibly brave, and you deserve the biggest applause for being so great.”

This message is praised by the teachers who hear it. It takes away the embarrassment or guilt and instantly makes the child a hero in front of the entire audience.

Interrupting the show for just a few seconds to fix something doesn’t hurt the pacing or detract from the performance in any way. It enhances your standing in the eyes of everyone as you show compassion and understanding to your young helpers.

Sadly, I had to learn this lesson the hard way. In the early 1990s, when I was touring with Chevrolet and performing as a magician for their car shows, I decided to incorporate a guillotine illusion into my show. This involves clamping a volunteer into a set of stocks and magically thrusting a blade through the volunteer’s neck. I’ll never forget selecting an eager young man who boldly knelt down and took his position. During the next minute or two of my banter, the boy became frightened and began to cry.

Instead of acknowledging this, I finished the routine and sent a visibly shaken child back to his family. This was a big mistake. It reflected poorly on me and certainly on Chevrolet. I should have taken better care of my volunteer, or at least reacted to the discomfort on the spectators’ faces and excused the child. I felt terrible and still hold that memory as a lesson learned. Because of that event, I’m now incredibly aware of my volunteers’ emotions when performing an illusion or stunt that could be perceived as scary or dangerous.

Famous comedian Robin Williams was known for his ability to see and hear even the smallest details in his audience. Famously, he drew on many of them in his improvisations. Assembly show performers need to develop the same ability, adding compassion, understanding, and patience. Teachers will recognize your skills and praise your ability to manage large groups of children ensuring a return engagement.